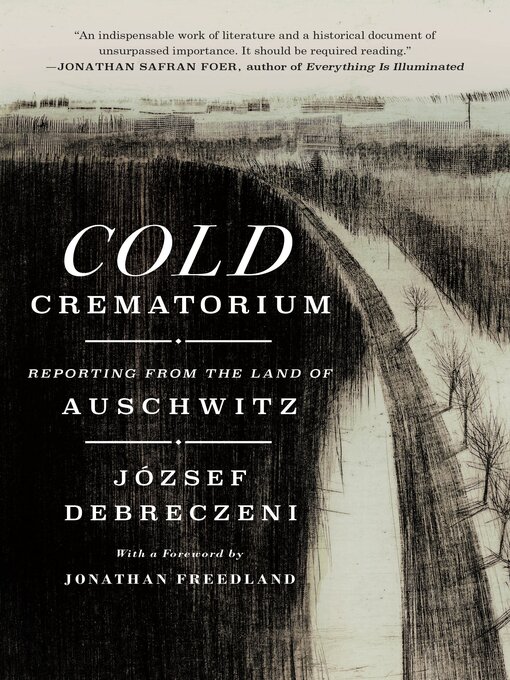

National Jewish Book Award finalist and one of the New York Times Book Review's 10 Best Books of 2024

A lost classic of Holocaust literature translated for the first time—from journalist, poet and survivor József Debreczeni

"As immediate a confrontation of the horrors of the camps as I've ever encountered. It's also a subtle if startling meditation on what it is to attempt to confront those horrors with words...Debreczeni has preserved a panoptic depiction of hell, at once personal, communal and atmospheric." —New York Times

"A treasure...Debreczeni's memoir is a crucial contribution to Holocaust literature, a book that enlarges our understanding of 'life' in Auschwitz." —Wall Street Journal

"A literary diamond...A holocaust memoir worthy of Primo Levi." —The Times of London

József Debreczeni, a prolific Hungarian-language journalist and poet, arrived in Auschwitz in 1944; had he been selected to go left, his life expectancy would have been approximately forty-five minutes. One of the "lucky" ones, he was sent to the right, which led to twelve horrifying months of incarceration and slave labor in a series of camps, ending in the "Cold Crematorium"—the so-called hospital of the forced labor camp Dörnhau, where prisoners too weak to work awaited execution. But as Soviet and Allied troops closed in on the camps, local Nazi commanders—anxious about the possible consequences of outright murder—decided to leave the remaining prisoners to die in droves rather than sending them directly to the gas chambers.

Debreczeni recorded his experiences in Cold Crematorium, one of the harshest, most merciless indictments of Nazism ever written. This haunting memoir, rendered in the precise and unsentimental style of an accomplished journalist, is an eyewitness account of incomparable literary quality. The subject matter is intrinsically tragic, yet the author's evocative prose, sometimes using irony, sarcasm, and even acerbic humor, compels the reader to imagine human beings in circumstances impossible to comprehend intellectually.

First published in Hungarian in 1950, it was never translated into a world language due to McCarthyism, Cold War hostilities and antisemitism. More than 70 years later, this masterpiece that was nearly lost to time will be available in 15 languages, finally taking its rightful place among the greatest works of Holocaust literature.

-

Creators

-

Publisher

-

Awards

-

Release date

January 23, 2024 -

Formats

-

Kindle Book

-

OverDrive Read

- ISBN: 9781250290540

-

EPUB ebook

- ISBN: 9781250290540

- File size: 4488 KB

-

-

Languages

- English

-

Reviews

-

Library Journal

August 1, 2023

A Hungarian-speaking journalist/poet who lived mostly in Yugoslavia, Debreczeni barely survived the gruesome selection process when he arrived at Auschwitz in 1944. After 12 months, he ended up in the so-called Cold Crematorium at the forced labor camp D�rnhau, where prisoners too weak to work awaited execution. He was saved when the Germans abandoned the camp as the Allies closed in. Published in 1950 but never translated, Debreczeni's memoir is now appearing in 15 languages worldwide. With a 60,000-copy first printing. Prepub Alert.

Copyright 2023 Library Journal

Copyright 2023 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

-

Kirkus

Starred review from November 15, 2023

An extraordinary memoir of the Holocaust by an unlikely survivor. Budapest-born Debreczeni was working as a journalist when the "gray ones" arrived, abetted by homegrown fascists and the German police in their "grass-green" uniforms. As his memoir opens, Debreczeni is on his way to some outpost of "the Land of Auschwitz" in a crammed cattle car. Most who survived the train ride landed in labor camps, where one might have died because "his cigarettes had been taken away," reason enough for the chain-smoker to give up on living. In a vivid rejoinder to Eugen Kogon's Theory and Practice of Hell, Debreczeni places the Nazis in the backdrop, with sadistic cameos, as when an SS officer asks a kapo who his best worker is and then shoots the unfortunate nominee in the head, saying, "An example of how even the best Jew must croak." Ever the intellectual, the author responds archly: "Kitsch. Horror is always kitsch. Even when it's real." The quotidian villains were the kapos, the Jews who, for a little extra bread and a few cigarettes, ran roughshod over the h�ftlings, or ordinary, prisoners. Whether merchants, doctors, or farmers, no class distinctions applied to a population meant to be erased once their usefulness as laborers had ended, even if the "camp aristocracy" assured that a chosen few favorites joined the kapos at "the footstools beside their thrones." Few h�ftlings survived, and Debreczeni was sure he'd die of starvation as he worked digging tunnels and building dams, dreaming of the day when he could "run amok taking revenge, calling to account, meting out justice to those who [had] dragged" him there. His revenge, one supposes, came in the form of this superb book, first published in Tito's Yugoslavia in 1950. An unforgettable testimonial to the terror of the Holocaust and the will to endure.COPYRIGHT(2023) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

-

Publisher's Weekly

February 19, 2024

Hungarian journalist and Holocaust survivor Debreczeni (1905–1978) recounts his experience of Auschwitz in this harrowing memoir, first published in Hungary in 1950. With a reporter’s keen eye for detail, Debreczeni recalls his 1944 arrival by train into the “broader archipelago of horror known as the land of Auschwitz,” a term he applies to the network of prison camps operated by Nazi forces in Poland and eastern Germany. Debreczeni was first assigned to work at a Gross-Rosen labor camp, where he found a subtle hierarchy—the “best” Jewish workers were camp clerks and junior prison functionaries, while “lazier” prisoners were their underlings. After making an error while blasting tunnels, Debreczeni was relocated several times before ending up at a hospital in Dörnhau, the eponymous “cold crematorium,” where his job was to compile daily reports on the number of dead and dying. Debreczeni describes in visceral language the quotidian details of life in a concentration camp (food arrives in “powder-grey, mud-heavy dollops”), and paints gutting portraits of his fellow prisoners, including a French lawyer who’s outlived his entire family. This sobering firsthand account of the Holocaust more than succeeds in its stated mission to “ the humanity of those forcibly deprived of it.” -

Booklist

October 21, 2024

This is a truly unique first-hand account of the Holocaust. J�zsef Debreczeni was a Hungarian-language journalist, poet, and novelist who lived in Budapest and in Yugoslavia. He was deported to Auschwitz, where he used his keen powers of observation and his literary skills to create a vivid and intimate account of the cruelty and insanity of the Nazi's ""Final Solution."" First published in Hungarian in 1950, Cold Crematorium is now available in a beautiful translation by Paul Olchv�ry. This is a real-time eyewitness history rather than a memoir reconstructed years later. It is a powerful, important document, especially at a time when anti-Semitism is increasing all over the world.COPYRIGHT(2024) Booklist, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

-

Formats

- Kindle Book

- OverDrive Read

- EPUB ebook

Languages

- English

Loading

Why is availability limited?

×Availability can change throughout the month based on the library's budget. You can still place a hold on the title, and your hold will be automatically filled as soon as the title is available again.

The Kindle Book format for this title is not supported on:

×Read-along ebook

×The OverDrive Read format of this ebook has professional narration that plays while you read in your browser. Learn more here.